Postage discount campaign!!!

This postage discount is limited offer!

If you purchase over ¥4000 JPY, you can get a ¥1000 JPY postage discount.

So don’s miss this chance to get japanese traditional crafts cheaper!

Postage discount campaign!!!

This postage discount is limited offer!

If you purchase over ¥4000 JPY, you can get a ¥1000 JPY postage discount.

So don’s miss this chance to get japanese traditional crafts cheaper!

We will be opening are store Ichipointin Shinjuku Marui Annex! !

It will be held in Shinjuku Marui Annex from September 27 (Wednesday) until October 7 (Saturday).

We are preparing many popular items of Ichipoints, such as “KOSHO <ougi> Tote Bag” which is also handled in MoMA in New York and stall of Kobo Bibai which is perfect for this season.

We are looking forward for everyone to come visit our store .We will be waiting with the extreme items selected by traditional handicrafts made in Japan from Ichipoint.

——————————-

● Store: Shinjuku Marui Annex 1F Event space

● Period: September 27 (Wednesday) – October 7 (Saturday)

● Time: 11: 00 ~ 21: 00

● Access:

1-minute walk from Exit C1 of Shinjuku Sanchome Station on Toei Shinjuku Line

Fukutoshin Line “Shinjuku Sanchome” Station B 2 Exit 3 Minutes Walk

6 minutes on foot from A6 exit at Marunouchi line “Shinjuku” station

——————————-

<Shinjuku Marui Annex HP>

https://www.0101.co.jp/005/?from=01_pc_st005_access_left-logo

The Way of the Artisan is an interview series in which we speak with master craftsmen from across Japan about the source of their creativity.

In our eighth installment we visit Toraya, a maker of wagashi, traditional Japanese confections, known to pretty much anyone in Japan, to speak with Minoru Masudo, a true artisan when it comes to making wagashi.

Toraya has been a beloved part of Japanese culture since it first opened its doors in Kyoto nearly 500 years ago during the late Muromachi Period. Given this steadfast history, just how does Mr. Masudo approach crafting confections at Toraya? He was quite happy to discuss some of the new challenges underway at Toraya as well. Furthermore, during the second half of the interview he even gave us a demonstration of how he makes the namagashi (fresh Japanese sweet) known as “sasaguri”.

Now without any further ado, let us delve into the world of Toraya.

It is said that Toraya was founded in the latter days of the Muromachi Period. Originally in service to the imperial household during the reign of Emperor Go-Youzei (1586-1611), Toraya then opened a second shop in Tokyo coinciding with the transfer of the capital there while also keeping their original location open in Kyoto. Toraya now maintains its head offices, factory, and a storefront near the Akasaka Estate (the Akasaka is currently undergoing renovations and is scheduled to reopen in 2018).

Minoru Masudo, our host for today, was first assigned to the manufacturing department of Toraya’s Tokyo factory in 1992.

“I decided to go with Toraya while I was job-hunting in school because of how simply beautiful the photos of namagashi looked in their company pamphlet. If it meant that I would have the chance to make things like that myself then I wanted to work there. I’ve always enjoyed making things since I was a child, whether it was plastic models of cars or just fooling around with woodworking.”

Mr. Masudo claims that once he starts making something he tends to go all-out. The origin of this trait can be found in his upbringing.

“My mother passed away when I was a fifth-grader in elementary school. That meant I often had to cook for myself even as a child, and may also be why I developed such an interest in food. The high school I eventually went to even had a department of food science, so I was just naturally set upon a culinary path.”

And thus Mr. Masudo found employment at Toraya. In the 17 years since then, he has remained at the forefront of confection-making. Each morning he enters the workshop at 7:30 to begin making fresh sweets to be sold in the shop that day.

“There are 46 people in my production team, with half working on fresh confections and the other half handling those sweets that must be baked. Just the fresh sweets for sale in our shops alone account for six or so different varieties. Each morning we’ll make on average 100 to 200 pieces of each variety. Once that’s taken care of we have a morning meeting followed by a break. Then we’ll do other things like start preparations for the next day’s work.”

When people think of namagashi, they tend to think of sweets designed to suit the season. Toraya rotates in seasonal confections at the halfway point of each month. The lineup for the second half of August 2017 includes delicacies full of seasonal flavor signaling that autumn has arrived like suisenmomiji-gasane (autumn leaf layers) or sasaguri, which Mr. Masudo made for us today.

Is there anything Mr. Masudo is particularly mindful of when making seasonal sweets?

“I try to really feel the seasons and observe nature in my daily life. If I just let the days pass by without really thinking about it, the whole year would end with me only saying ‘It’s hot’ or ‘It’s cold’. I make a conscious effort to look at flowers blooming along the roadside, to gaze at the sky and the clouds.”

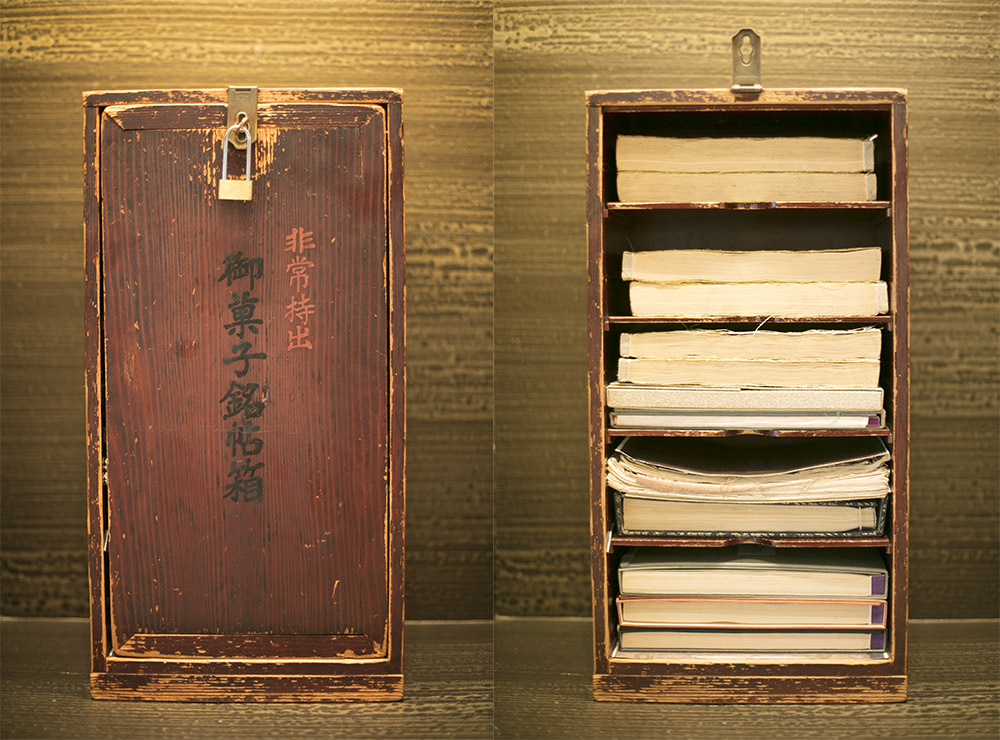

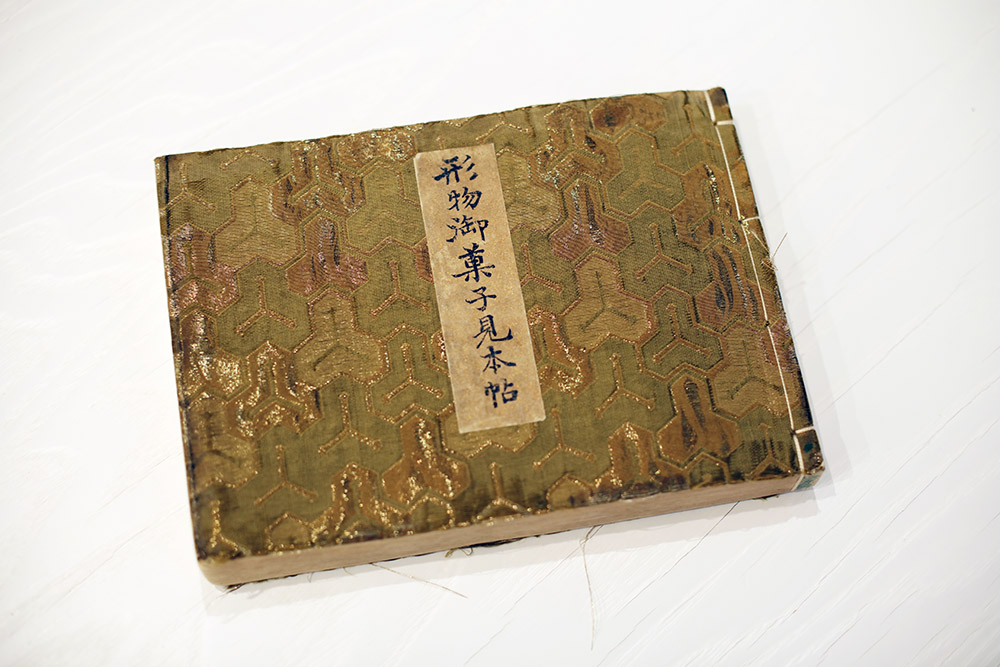

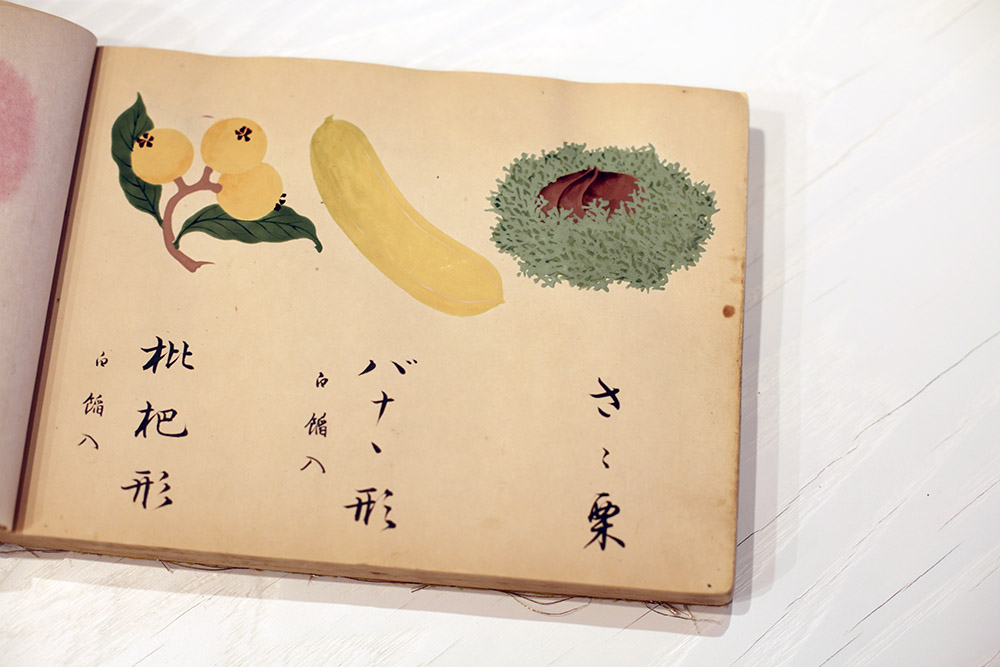

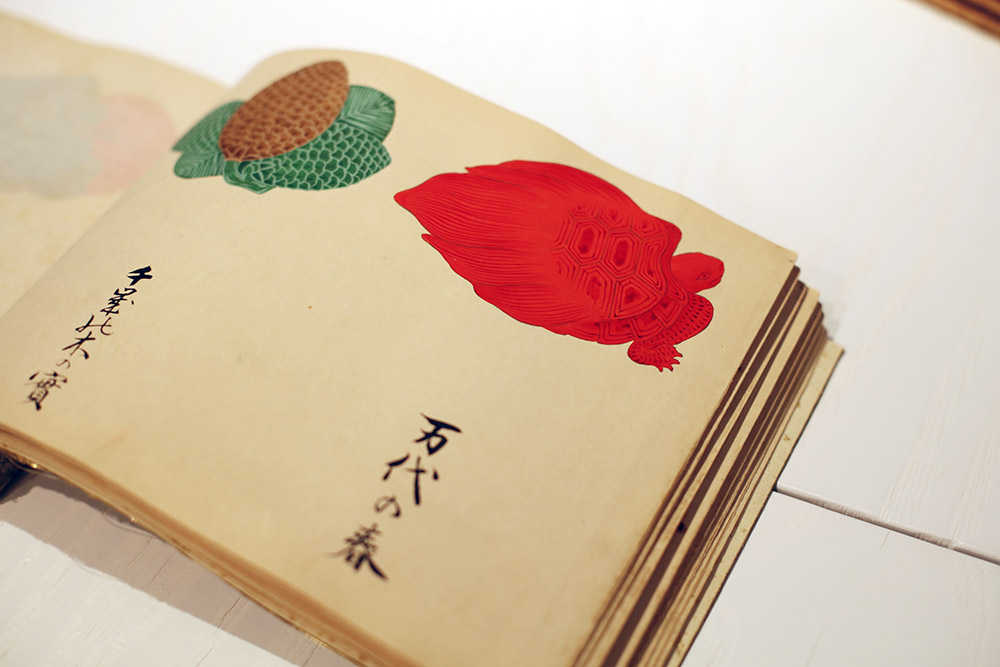

At Toraya there are illustrated wagashi design books that has been maintained for generations. They contain images and names of of Toraya’s creations, so they has often served the role of a product catalog in the past. The oldest existing delicacy detailed within them apparently dates back to the eight year of the Genroku Period (1695), so the sample books really remind one again of the long history of Toraya.

What’s even more surprising is that Toraya still makes Japanese delicacies based off of those found in these books. There are apparently around 3,000 different varieties of sweets recorded within them!

Though Toraya has been a beloved favorite of people in Japan for nearly 500 years, Mr. Masudo states that it is still important to question and rethink their way of doing things and the flavors they have created up until now.

“One of the first things the current head of the company (Mitsuhiro Kurokawa, the 17th-generation owner of Toraya) did upon assuming the helm was start investigating whether our flavors here were infallible. He had employees wear blindfolds and try yokan (gelled sweat bean paste) from other brands, including our own, and then asked everyone what they thought. With such a long history, there are more than a few things at Toraya that tend to get taken for granted or people have come to believe. While the flavors we produce here are those built up by our predecessors, Mr. Kurokawa says that it is also perhaps beneficial to tweak these flavors a bit at a time so that they better fit the times.”

Mr. Masudo was focused solely on making sweets after coming onboard at Toraya in 1992, but in 2009 he moved to the public relations department. After making things for 17 years he suddenly found himself in the place responsible for helping spread the word about Toraya to other people. Just what exactly did this entail?

“When guests come and see how we do things here, the best way to make sure they understand is to give them an actual demonstration rather than simply relying on words and pictures. That’s why Toraya has always made sure there is one person on the PR team that can actually make confections themselves. At the time that role fell on my shoulders.”

Mr. Masudo found himself wondering why he was chosen as he made his transition to PR. He went from his old position of being an expert at making sweets to one that required him to be able to explain not only the history of Toraya but also about the company as a whole, which apparently meant that he learned more than a few new things along the way.

“I returned to manufacturing department after two years in the PR department. Then, four years later I was placed in a role of training my juniors as the one responsible for improving techniques in production. My experiences learning how to share information with others as a member of the PR department came in very handy while doing this.”

Mr. Masudo is now the head of production. He works with his team making sweets, and is also in charge of administrating the factory as a member of management. Now then, let’s have Mr. Masudo make one of Toraya’s season namagashi for us!

…You have a completed sasaguri!

…You have a completed sasaguri!

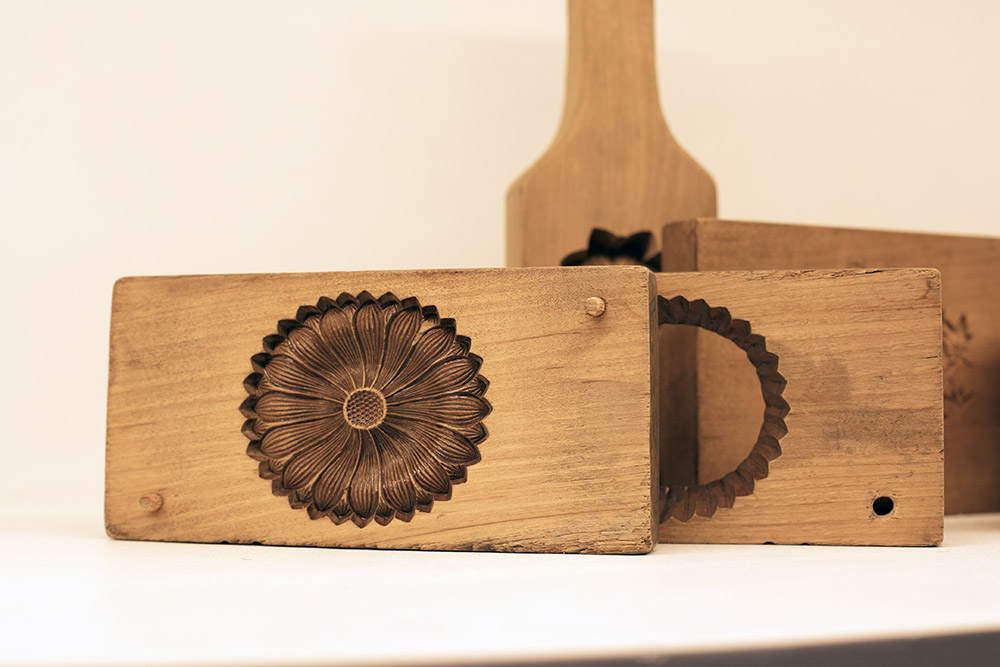

Sasaguri features some complex shapes, and the amount of restraint that needs to be applied means that it is apparently quite difficult to make despite how simple it looks. The chestnut portions of this delicacy are given a sheen by applying melted treacle with a brush. Applying the “soboro” that is the finished touch of this delicacy requires the utmost restraint to ensure that each strand doesn’t get crushed. It supposedly takes a year of training before one is capable of making sasaguri that is fit to put on display in a storefront.

What’s even more astounding is how amazingly real the chestnuts in the dish look! The showy look of sasaguri truly catches the eye, even in the old images found within the confection sample books. The true charm of Japanese confections that tickles people’s fancies isn’t found just in the way they represent nature, but also perhaps in their shapes and colors that act in concert with the current season.

Toraya’s lineup of namagashi rotates every half month in order to keep up with even the slightest shift in seasons. With this in mind, it might be possible to encounter new tastes while snacking on these Japanese savories.

Sasaguri, the seasonal sweet from Toraya featured in this article, is available at their locations from August 16 (Wednesday) to August 31 (Thursday). Don’t miss the chance to experience the texture of the carefully wrapped “chestnuts” and the soboro, which requires such precise restraint in order to resemble the case, for yourself.

Ichi Point also has a selection dishes that are perfect for enjoying Japanese sweets. Be sure to find a set to go along with some delicacies from Toraya.

The Way of the Artisan is an interview series in which we speak with master craftsmen from across Japan about the source of their creativity.

The fourth through seventh installments are a Hokuriku special celebrating the first anniversary of the Hokuriku Shinkansen. For our sixth installment we visit Kunichika Tsurumi, a second-generation Kaga-Yuzen silk dyer at the Tsurumi Dyeing Arts workshop in Kanazawa City, Ishikawa Prefecture.

Born into a family that has been working with dyed goods for generations, Kunichika studied Tokyo-Yuzen silk dyeing after graduating from the Department of Fine Art at Kyushu Sangyo University. He then went on to apprentice in the ways of Kaga-Yuzen dyeing under his father, Yasuji Tsurumi. He now works as a full-fledged Kaga-Yuzen artist.

“The Kaga-Yuzen style of silk dyeing has a history spanning nearly 300 years. During the Edo Genroku period Yuzensai Miyazaki, a popular painter from Kyoto, brought his silk dyeing techniques to Kanazawa. This style, Yuzen dyeing, is named for him,” states Kunichika.

Let’s start by learning what makes Kaga-Yuzen different from other styles of dyeing.

“There are three main schools of Yuzen dyeing – Kyo-Yuzen, Kaga-Yuzen, and Tokyo-Yuzen. Each of them originates in a different region, but Tokyo-Yuzen is perhaps the most stylish. Kyo-Yuzen is very flashy with lots of gold and embroidery. And then we have Kaga-Yuzen, which features subdued floral patterns dyed only with colors.”

“I dye the silk by placing paste around the lines of the drawing and then filling in the colors. Some techniques distinct to Kaga-Yuzen silk dyeing are ‘mushi kui’ (bug-eaten), which involves leaving marks like those of a bug eating a leaf, and ‘saki-bokashi’, which involves shading the drawings starting from the outside and working inwards.”

Yuzensai Miyazaki, said to be the originator of Yuzen silk dyeing, was born in Noto, Ishikawa Prefecture.

After making a name for himself in Kyoto as a fan painter, Yuzensai returned to Kanazawa in his later years. He joined ‘Taro Taya’, a leading dyer under the Kaga clan, and went on to create innovative designs for kimonos based upon Kaga dyeing techniques. His style would go on to become the cornerstone of Kaga-Yuzen dyeing.

Kunichika’s great-grandfather Takichiro Tsurumi inherited “Taro Taya”, the dyeing workshop that Yuzensai joined in his final years. In other words, Tsurumi was born into a lineage that has a direct connection to the origin point of the Kaga-Yuzen style.

Obviously each and every one of these images is hand-drawn by the craftsmen. In other words, Yuzen dyeing is a very time-consuming process. Just how long does it actually take?

“A single design generally takes three months to complete. At our workshop we generally work on four or five designs at once, so we usually produce 30 or 40 kimonos a year. My father is registered with the Kaga Zome Promotion Cooperative Association as a Kaga-Yuzen artist, so the kimonos we make bear the association’s official seal of approval. My wife and one other employee also work with us, so in total there are four of us doing this for a living.”

[caption id="attachment_5194" align="aligncenter" width="650"] Kunichika’s father Yasuji was commended with the Ishikawa Prefecture Cultural Service Award, making him one of the foremost Kaga-Yuzen artists in Kanazawa.

Kunichika’s father Yasuji was commended with the Ishikawa Prefecture Cultural Service Award, making him one of the foremost Kaga-Yuzen artists in Kanazawa.

So it takes three months of work before a single Yuzen dyed kimono is completed. One has to wonder what the price range for them is like.

“We’ve recently been making some kimono using ink jet printing, and these generally run upwards of ten thousand yen. It depends on the design, but some of our true Kaga-Yuzen kimonos made by hand can cost over three million yen.”

“Kimonos sold the most during the Bubble. The price has continued to go down slightly since then. More people are wearing kimono now, but many of them are antiques. So the state of the luxury kimono market is changing even further.”

Does Kunichika’s workshop only handle kimonos? Why are they so particular about hand-dyeing?

“Up until now we only worked with kimonos, but we recently began doing fans, stoles, and other accessories. In technical terms, hand-dyeing often produces a certain non-uniform look, whereas inkjet dyeing produces an even, uniform finish like that of a flat surface. That’s the main difference between them at this point.”

So what makes true Kaga-Yuzen dyeing so distinct from other types of dyeing?

“Hand-dyeing has a certain artistic flair to it with some areas seeming more strong and others weak, rather than having a even look. When it comes time to pick a kimono, it is these touches that reach out and stimulate the wearer in an invisible manner when they actually wear it or see how they look with it on in the mirror.

In order to learn painting, Kunichika went to two classes while studying carpentry sketching and watercolor painting since he was in high school. After finishing university he was at first resistant to inheriting the family business and instead found work elsewhere. But, in the end he returned to take up the family trade. He has now been doing hand-dyeing for a quarter of a century.

“Generally I do the same thing day in and day out. Sometimes I wish I could somehow change things quickly, but something that has existed for 300 years like this can’t be changed overnight. I approach each project individually, knowing that I’m growing even though I can’t see it.”

Finally, what does Kunichika hope to share with the world through silk dyeing?

“Dyes have a transparency to them. I hope to create kimono clear, beautiful kimono that will connect with the wearer’s heart.”

Technological progression is pushing society forward and is on the verge of changing the history of traditional crafts. There is much to be learned from the master artisans who uphold what needs to be upheld while still keeping their ears open to the signs of the times.

Here at Ichi Point we will continue to support Tsurumi Dyeing Arts and Kaga-Yuzen silk dyeing.

We have introduced three craftsmen from Hokuriku in installments four through six of Way of the Artisan, the interview series in which we speak with master craftsmen from across Japan about the source of their creativity. Next time in installment seventh we speak these three craftsmen about a unique product that combines all of their skills, so stay tuned.

The sakura are in full bloom, and it’s a warm spring day with clear skies.

Today we visit Asakusa, a tourist destination popular with both Japanese and visitors from overseas.

Today Urara, a reassuring guide who knows everything about Asakusa, joins us on our stroll. Urara once worked in Asakusa as a “furisode”, a type of dancer brought in by restaurants to entertain guests similar to the apprentice geisha found in Kyoto, but without the same stringent thresholds.

Furisode are also often called upon to perform at banquets in smaller restaurants or hotels, as well as other distinctly Asakusa-style celebrations like succession parties for hanashika (comedic storytellers).

Our meeting place was the Asakusa Culture Tourism Center, a tourist guide facility located right in front of the Kaminarimon gate. We chose this spot because the top floor has a viewing terrace that Urara highly recommends.

“You can see the entire Asakusa neighborhood. I always start here when showing people around the area.” With that said, we began our walk by following Urara up to the top floor to take a look at the area we were going to explore.

Snacking on Nakamise Street

Asakusa is full of tasty things to eat. During our stroll of the neighborhood Urara was constantly giving us foodie info saying this or that place was good.

Our first stop was Kameju, a Japanese confectionary shop next door to our starting point at the Asakusa Culture Tourism Center.

“The dorayaki here is amazing! The skin is fluffy and the dough is just like an egg,” says Urara.

We set off to pick up some, but it turns out that the Kameju’s dorayaki is so popular that people line up to buy it. According to one of the staff they sell out as early as just after noon, so if you have your heart set on eating some of their dorayaki then it might be best to order ahead (this needs to be done several weeks in advance, however).

Next we headed for Funawa, which is found on Nakamise Street on the way to Asakusa Temple. While many people are most likely familiar with Fuanawa as a famous chain shop with locations all over Japan, Urara still recommends it for the following reason: “Funawa’s sweet potato paste and anko-tama are familiar choices, but did you know they also have yaki-imo daifuku? These were way more popular with my furisode friends. I think Funawa should push their yaki-imo daifuku harder.”

If it’s some of Asakusa’s famed ningyo-yaki you’re after, then Urara recommends the cute-shaped sweets of her favorite spot, Kameya. They have a shop on Nakamise Street where you can see the ningyo-yaki being made.

One thing you’ll see a lot of wandering around Asakusa is friend manju. As a local speciality offered by many shops it can be choose where to buy from, but Urara suggest Asakusa Kokonoe on Nakamise Street.

As she told us, “If you forget where it is just remember that it’s the closest shop to Kannon (Asakusa Temple).”

Lunch, dinner, tea, and then some sake.

Eateries chosen after some careful thought

For lunch we went to tonkatsu specialists Tonshou. The reason we chose them out of all the other options available is that Takao Iida, the owner of Ichibanya, a charcoaled senbei shop on Nakamise Street, recommended them. Mr. Iida is the director of the Nakamise Shopping District Stimulus Association, and Urara and he are such good friends that they call each other “Takao-chan” and “Shishimaru” (Urara’s stage name during her furisode days). Mr. Iida is also a foodie, so we decided to stop by and ask for some tips while we were out on our stroll. As it happens, after Urara retired as a furisode dancer, she changed her name to “Kaguya-onna no Urara” and moved to a more fixed setting, but in her words, “Everyone in Asakusa still calls me Shishimaru.”

Inside Tonshou with us were a couple of older gents who seemed to be locals chatting over lunch and another man who seemed to live in the area ordering something not found on the menu. While the tonkatsu is delicious, it’s scenes like this that really make this restaurant feel firmly rooted in the community.

For dessert we stepped over to Japanese sweets shop Umemura. The interior is simple and unaffected, with six seats at the counter and three tables on tatami. Seeing the way what seemed to be regulars greeted the staff let us know that we were in one of the locals’ favorite spots.

As Mr. Iida from earlier puts it, “Asakusa has a lot of coffee shops.” And as his words imply, there are indeed many coffee shops in Asakusa that have a unique atmosphere quite unlike that of regular cafes that is fun to enjoy.

Our choice from the bevy of shops available was Royal Coffee Shop.

Upon stepping inside the shop we immediately knew we were in a coffee shop from size of the tables and chairs, the color of the lighting, and the look of the menu. There were men drinking coffee as they read sports newspapers, older women chatting away, and elderly men eating coffee and cake, which all helped contribute to the old school coffee shop atmosphere.

It was dinner time, so we moved on to Unagi Koyanagi, an old eel cuisine restaurant that Urara had often been invited to dance at. Unagi Koyanagi is a popular destination for celebrities such as kabuki actors. While kimo-sui (eel-liver soup) costs extra, Urara says, “The price of Koyanagi’s kimo-sui has always been 100 yen since the day the restaurant opened. They have had to raise the price of their other unagi dishes, but the owner apparently wants to keep the soup at the same price.” We recommend taking advantage of his kind disposition and ordering some kimo-sui along with your meal.

The final stop on our exploration of Asakusa is Kamiya Bar. This is Japan’s first bar, a favorite haunt of literary masters that is home to the famed “Denkin Bran” cocktail.

The interior has tables scattered about that are filled with people popping in on the way home from work and assorted regulars. It truly has the feeling of a place of social intercourse for the older part of town. We of course bought a Denki Bran, and when we chatted up the older fellow drinking by himself in the seat next to us the conversation started up quite normally and he ended up joining us. He ended up being a very unique guy, and a bit much in the end, but this sort of encounter is one of the charming parts of Asakusa.

Enjoy the unique entertainment of Asakusa

When it comes to entertainment in Asakusa, the two most famous locations are Asakusa Engei Hall for enjoying rakugo, and Toyokan, which features mainly manzai and stand-up comedy. But, since we had a someone with such a thorough knowledge of Asakusa with us like Urara, we decided to go somewhere a bit more underground.

The first place we went was the public theater Mokubakan. Public theaters are places where visitors can see period plays, dances, and song shows. Mokubakan brings in a new theater troupe each month and holds performances at twice a day at noon and night, but the surprising thing is that the musical program changes every day. Urara says, “The dancing and plays are extremely well-performed, and you can see them all for less than the price of a movie ticket.” The wooden clappers sounded and the stage curtain rose, signaling the start of the show. The dancing to music was amazing, and the play had an easy plot that had us thoroughly engrossed.

The next secret spot we visited was the Edo Shita-machi Traditional Arts Museum, where you can see the techniques passed down among craftsmen here from the days of Old Edo along with works made using said skills. You can go peruse the two floors of normal displays featuring various traditional creations like mikoshi shrines, copperwork, and paulownia cabinets. On Saturdays and Sundays the first floor hosts presentations by artisans, so it’s also fun to come just to see these masters at work firsthand.

Urara’s recommended spots

Food

●Tochigiya – tofu and raw bean curd

“Their tofu refuse donuts are delicious,” says Urara. When we looked in the store we could see fresh donuts on the counter.

● Milk no Ki – Western confections

“All of the furisode girls order their birthday cakes here.” The honey apple pie looked tasty.

● Chibaya – candied sweet potato

While there are other candied sweet potato shops in Asakusa, Urara recommends this one because, “It’s not part of a chain. This is the only location.”

● Yagenbori – pepper and spices

The pepper comes gourd-shaped containers, so Urara often uses it as a present. “They can adjust the mix to suit any preference, so you can choose how hot you want it to be.”

● Lodge Akaishi – coffee shop

This shop stays open until the wee hours of the morning (1am on Sundays and holidays), so it’s known as a haunt for taxi drivers. “They have a big menu, and make whatever you ask for.”

● Brazil – coffee shop

Mr. Iida of Ichibanya recommended this coffee shop. “You have to get the chicken basket at Brazil! Oh yeah, the pickled carrots are also great,” says Mr. Iida.

Other spots

● Fujiya – dyed towels

Here you can get cool and classy towels decorated with patterns from Edo era fashion or seasonal flowers. As Urara puts it, “The pattern on the curtain out front is called ‘itoshi fuji’. The ‘i’ and ‘to’ characters lined up with the vertical ‘shi’ resemble a wisteria flower. So they’re representing love (itoshi in Japanese) with a wisteria flower.”

Sights

● The wisteria flowers of the Hatsune Shoro Restaurant District

Shelves of wisteria line the streets here, and around the beginning of May begin to show beautiful pale violet flowers. According to Urara, “It gets a bit shady here at night, so it can be somewhat scary (laughs).”

Tips for strolling Asakusa

● Use side streets when walking down Nakamise Street

After passing through the Kaminarimon Gate, you will see Nakamise Street, the main path to Asakusa Temple. This street is always crowded, making it hard to walk as you want.

If you already have a destination in mind, then we recommend using one of the side streets running along both sides of Nakamise Street.

● Be careful about coming on a Monday

Many of the shops in Asakusa are closed on Mondays, so make sure to check beforehand if the shop you’re interested in will be open.

● Visit Asakusa at night, too

Asakusa has a light display everyday from sunset to around 11pm. The crowds of tourists also thin out at night, so things are a bit calmer. You can enjoy a nice view of the main temple pagoda, as well as the Sky Tree glowing in the distance.

Type your keyword and hit enter button for result