Noriko Matsui

The sixth-generation apprentice of Matsui Silk Weaving

Photos by Tomo Kosuga Text by Tomo Kosuga

“The Soul of Takumi” is an interview series in which we speak with master craftsmen from all over Japan about the source of their creativity. Our fourth through seventh installments will be part of a special focusing on the Hokuriku region to commemorate the first anniversary of the Hokuriku Shinkansen. This time around we interview Noriko Matsui, the sixth-generation apprentice of Matsui Silk Weaving, which is located in Johana in Nanto City, Toyama Prefecture. With a cute demeanor and a boisterous laugh, Noriko has the type of smile you don’t forget.

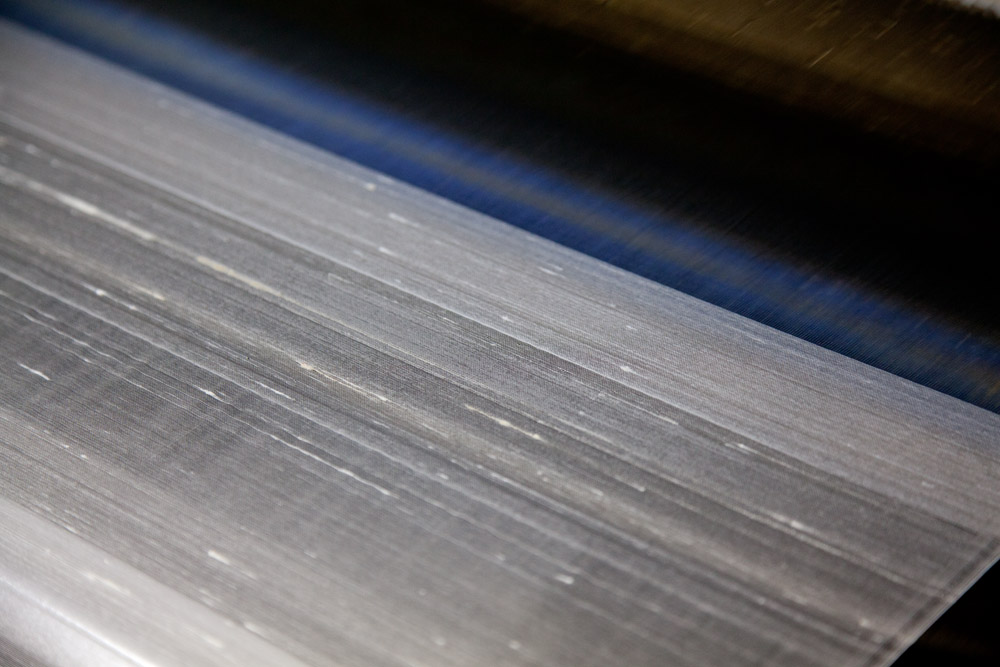

Matsui Silk Weaving has been producing silk textiles ever since its doors opened in 1877. They have devoted special effort to the production of Johana shike silk, which is woven from miraculous dupion silk threads, which comes from the joint cocoons of two or more silkworms.

Shike silk, a fruit of love

More than a few of us probably raised silkworms back during elementary school. You feed the white larvae mulberry leaves, and eventually they make a cocoon and become pupae. Silk is made from these cocoons.

“Each worm makes a single cocoon. But, very rarely two worms will make a single cocoon together. We call this a ‘tama mayu’ (ball cocoon), and the silk we weave from the “tama ito” (ball thread) that comes from these cocoons is referred to as ‘Shike silk’. It’s a fruit of love born from two silkworms,” explains Noriko.

As the name “ball thread” suggests, this type of thread is dotted with knobs. Once woven into fabric, these knobs give the silk a distinctive look.

Silkworms produce tama mayu at a rate of around two to three per 100 cocoons. Tama ito was once referred to as “suji silk” (knobbed silk) and in fact generally sold for less, it is now valued for its rarity and unique look, so both tama mayu and tama ito are worth a good amount today.

5,000 years of history between humans and silkworms

According to The Dainippon Silk Foundation’s “History of Silkworm Culture”, the connection between humans and silkworms is very ancient, beginning nearly 5,000 years ago when the Chinese first began cultivating them along the Yellow River or in the Yangtze valley. The practice then spread to Rome through the Middle East in around 200 B.C during the days of the Han Dynasty. This trade route would eventually become known as the ubiquitous “Silk Road”.

“The wonderful thing about silk is the way it allows light to pass through. If you shine light on polyester it only passes through one way and is bounced off. Silk, however, is composed of countless fibers, which are actually triangle-shaped. This produces a diffused reflection, much like a prismatic effect, and this in turn is what gives it such a glossy surface. Even the brightest of light becomes very soft once passed through silk.”

Silk weaving became mechanized in Japan at the end of the Edo period, and in the Meiji era the Tomioka Silk Mill was built and went on to greatly improved silk technology in many locales. Silkworm farmers producing cocoons all over Japan also spread throughout Japan, and by 1930 so much of Japan was invested in silk production that 40 percent of all farmers were raising silkworms.

Unfortunately various factors such as the spread of synthetic silk would lead to the eventual decline of the silk industry. Now there are only several hundred silkworm farmers left in all of Japan. Matsui Silk Weaving is the only one manufacturing shike silk, and also the only one to use time-honored method of applying the silk to Japanese paper after it has been woven, refined, and dyed. One has to wonder how Noriko feels as the sixth-generation head of the family business in such dire circumstances.

An hour of conversation that changed a life

Perhaps the most surprising thing is that Noriko only recently began thinking about the family business. Born the third daughter in the Matsui Silk Weaving family, Noriko enrolled in a private university in Tokyo after graduating from a local high school. She then took a sales position at a brokerage.

“My parents told me they wanted me to come back after I finished college. But they were also nice and would also say that instead of coming back straight away it might be best if I experienced living in Tokyo as an adult (laughs).”

Noriko claims that she had absolutely no interest in the family silk business at that time.

“I couldn’t see it as anything but a dying industry that produced outdated things. So I had no intention of inheriting the family business. My public and private life in Tokyo was so fulfilling that everyone who knew me called me “the person least likely to return to his or her hometown.”

The turning point for Noriko came in 2009.

Her father Fumikazu Matsui, the fifth head of Matsui Silk Weaving, came to Tokyo to visit some clients and invited Noriko along thinking that she might learn something interesting. This one conversation that Noriko joined out of sheer curiosity ended up changing her life completely.

“During this hour-long conversation I learned how wonderful silkworms are. Silkworms are an even older kind of livestock that pigs or cattle, and that they are counted in the same manner. Also that raw silk can cut ultra-violet rays, and that it can absorb ammonia and makes adjustments by absorbing or expelling moisture. That’s how much potential this fabric has! It seemed so dazzling to me. It was the first time I felt I wanted to get involved in the business. I just felt this wave of inspiration overtake me.”

Kindred souls spinning tama ito in Brazil

You only live once. There are no rehearsals. Noriko made up her mind – if not now, then when would she ever go back? She decided to make a U-turn right away. She told her parents that she wanted to succeed the family business at the end of that year, and left her brokerage job at the end of March the next year. Straightaway Noriko went to Brazil the next month in order learn weaving firsthand. But why go to Brazil?

“The fact is that the tama ito we use here at Matsui Silk Weaving comes from Brazil. Raw silk is fine, but since tama ito requires two worms there is a very low chance of it being produced. The fact of the matter is that there is none being produced in Japan now. But there are Japanese who immigrated to Brazil 100 years ago, and there was once apparently even a village named Bastos where the people spoke Japanese. I went to visit a silk weaving company named Bratac that was founded there. The head of their workshop is Japanese. There are people there who went all the way to Brazil after finishing college in Japan.”

What Noriko encountered in Brazil was a kindred spirit who exhibited the spirit of Japanese craftsmanship that she was looking for. She also found one of the merits of working with a Japanese to be the ability to communicate minutely.

“Say for example I say that I want tama ito that is so healthy it looks ready to burst. This is the type of nuance a Japanese would understand most easily. Their ability to understand these things as they work with us is part of the reason our relationship continues to this day.”

Giving shape to things you can only hear here

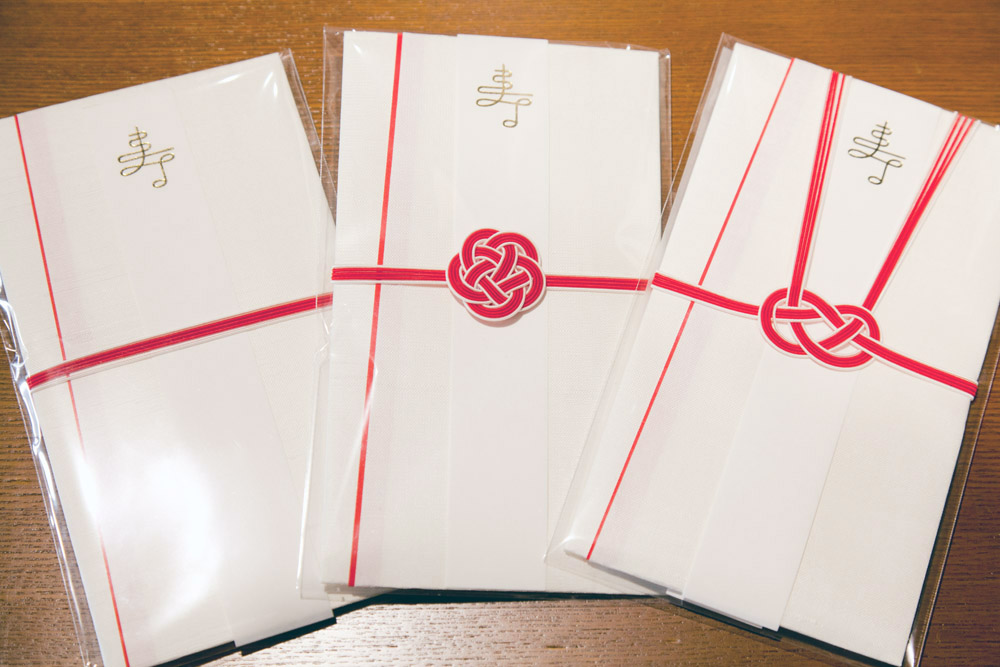

Upon returning to Japan after strengthening ties with the people supporting her family business on the other side of the planet, Noriko threw herself into developing tangible products for end users. In 2012 she held a month-long exhibition at River Retreat Garaku, a luxury hotel in Toyama, followed by showings at Seibu Shibuya and Tokyo Big Site.

“We only make very thin fabric. That’s why even when we approach wholesalers who work with fashion brands they tell us our silk won’t work since it’s too fragile. The only person who said they could use it was a haute couture dressmaker. There is no winter in the world of haute couture. Even though our fabric is translucent they said it was very beautiful. That made me realize for the first time that some people in this world got what we were trying to do.”

Noriko became fully engrossed in the silk business as she took on tall orders and gave careful attention to each client. However, she says there came a point where she ran into a question that she couldn’t find an answer to just by pursuing what was before her.

“When I spoke with other people involved family craftwork businesses that span generations or shrine carpenters, I found that the thing they’re most concerned about is what others will think about their handiwork 100 or 200 years down the line. Their rivals are craftsman from 100 years earlier and 100 years in the future. When they told me these things I felt very overwhelmed.”

“I remember saying to myself, “What can I do?” to myself as I prayed at my grandfather’s altar. Looking around myself afterwards, my eyes fell upon a fusuma sliding door made of shike silk. I knew then that this was something I had to share with later generations. So I started to think of what moments shike silk really shines the most.”

“I am the sixth-generation of our family devoted to shike silk. There is something I feel here that can’t be seen with the eyes. A voice that I can hear when I open my ears. I realized that I needed to feel this day by day, explore new forms of beauty, and study the history of Johana.”

A dream of weaving silk made in Nanto City

The father and fifth-generation silk weaver in whose footsteps Noriko is now following is currently 67 years old. Her mother, who helps out at the workshop, is 61 years old. While they both still desire to be actively involved in the production process, their time is limited. Despite this Noriko has chosen to focus on the future and press onwards.

“My dream is to weave silk made in Nanto. Mayor Tanaka was kind enough to come on board my idea. He said, ‘A beautiful future can be found in the dear past.’ They are trying to build a small, recycling-oriented eco village equipped with hydraulic and solar power generators in Sakuragaike. That’s where I intend to bring back silkworm farming.”

“At the same time I also go to ‘90s testimonials’. Nowadays we can’t live without electricity, but back before the war some people managed without it. That’s why I listen to people in their 90s speak about life before the war. I want to find ways to put that information to use today. There was someone who had been a silkworm farmer until just recently. I want to utilize that knowledge and get involved in farming myself.”

It would seem that it won’t be long until we see the silkworms that were once raised in the triangular villages of Nanto surpass the boundaries of time to spread their white wings once more today. And there is no doubt that the one warmly caring for them will be Noriko Matsui, the sixth-generation head of Matsui Silk Weaving who brings so much life to the people of Toyama and Johana with her lively laughter.

Matsui Silk Weaving

www.shikesilk.com

Matsui Silk Weaving has been in the silk trade ever since their doors opened in 1877. They use shike silk to produce interior goods, mounting fabric such as nanako and brocade gauze, and small woven items like komaro used as summer undershirts for kimono.

Noriko Matsui

stylestore.jp/blog/user/T00665

After 8 years living in Tokyo, Noriko Matsui experienced a U-turn in her life when she fell in love with silk weaving and decided to take the helm of the family business, Matsui Silk Weaving, which was founded in 1877. Her feeling towards Johana and craftsmanship grew stronger day by day as she studied on-site, and she now realizes the fun of pursuing her trade in her hometown.